Could a credit downgrade be worth it?

A cost-benefit analysis of debt financing for climate infrastructure

- In the upcoming decades, municipalities across the country may have to take on large amounts of debt to build climate mitigation and adaptation infrastructure.

- Some municipalities may hesitate to issue the debt required to finance these projects due to concerns about being over-leveraged and the associated negative implications for their credit profiles.

- Using the city of Virginia Beach’s recent flood mitigation bond as a case study, our analysis demonstrates that when the full costs and benefits are considered, funding climate adaptation infrastructure may be worth it — even with a downgrade.

In recent years, extreme weather events and natural disasters have impacted cities across the United States: Hurricane Sandy caused billions of dollars in damage to New York and New Jersey in 2012;1 the Missouri River floods in 2019 drove billions in economic losses;2 and 2023 flooding in Vermont left much of the state capital underwater.3 Today, California’s wildfire risk is so high that some large insurers are no longer issuing homeowners policies in the state, and losses from wildfires in the greater Los Angeles region in early 2025 may exacerbate this trend.4,5 Other areas of the country are facing the more chronic climate-related stressors of increasing heat, water stress, and droughts.

These climate-related events can have long-term impacts on the affected communities. Hurricane Katrina, which caused over 1,000 deaths in New Orleans in 2005,6 also led to a mass migration of city residents. Other cities have experienced economic hardship: the city of Clyde, Texas, recently defaulted on its water and sewer system bonds and cited ongoing drought conditions in the area as one of the reasons for its financial difficulties.7 Five years after being ravaged by a wildfire in 2018, the town of Paradise, California, defaulted on previously issued refunding bonds in 2023.8

In the face of these chronic and acute risks, many towns and cities are updating their climate adaptation plans. Some are considering land-use and zoning changes, while others are weighing the costs and benefits of larger-scale infrastructure projects like raised highways, levees, sea walls, and oyster reefs. Because the upfront costs of climate adaptation infrastructure are high — a proposed sea wall for Charleston, South Carolina, has an estimated price tag of around $1.3 billion9 — many local governments are turning to the municipal bond market for financing options. This trend is likely to accelerate. According to a report by Municipal Market Analytics in March 2024, municipal bond issuance may grow by as much as $800 billion by the 2030s due to climate infrastructure needs alone.10

However, individual municipalities may hesitate to issue the large amounts of debt required to finance these projects because credit ratings agencies incorporate liabilities into their ratings assessments. S&P, for example, states in their methodology that debt and liabilities represent 20% of an issuer’s credit profile.11 Incorporating debt and liability considerations in credit rating methodologies makes sense: too much leverage can often be associated with default, as was the case with Puerto Rico and Detroit, Michigan.12

At the same time, ratings agencies have published reports explaining that climate change may represent an increasingly negative credit factor for issuers that do not have sufficient mitigation and adaptation strategies in place.13 From the issuer perspective, this presents a difficult trade-off: large amounts of debt may be necessary to build climate mitigation and adaptation infrastructure, but that same debt could lead to negative implications for their credit rating. Issuers are left weighing three different considerations: vague encouragement from credit agencies to invest in climate adaptation; specific information about the negative consequences of being over-leveraged; and the potential economic and life-saving benefits of climate adaptation infrastructure.

Below, we show that the fear of being over-leveraged may be short-sighted. When the full costs and benefits are considered, funding climate adaptation infrastructure may be worth it — even with a downgrade.

Case study: Virginia Beach

For the past several years, coastal Virginia has experienced the highest rate of relative sea-level rise on the entire U.S. Atlantic Coast.14 In 2021, in response to growing concern about recurrent flooding, voters in the coastal city of Virginia Beach approved a $567.5 million flood mitigation municipal bond. The bond prioritized 21 flood mitigation projects, including drainage improvement projects such as culverts, road elevations, and pumps, as well as natural infrastructure projects like marsh restoration.15

In the lead up to the vote, Old Dominion University published a report analyzing the potential impacts of the flood mitigation projects. The report found that, with no intervention, the value of losses from floods from 2021 to 2069 would be projected to amount to $4.6 billion (in 2021 dollars). This number does not include the estimated net present value of declines in economic output due to flooding, projected to be an additional $6.5 billion loss over the same time frame (in 2021 dollars).16

The report also examined the potential benefits of the projects, estimating that their construction could raise economic output by over $371 million and create ~3,300 jobs in the next decade.17 The costs to residents are relatively modest in comparison: to pay for the bonds, the city is increasing its real estate tax by 4.3 cents per $100 of assessed house value, an increase of ~$115 per year for the median homeowner.18

Figure 1. ICE Flood Scores by census tract in the Hampton Roads region of Virginia. Source: ICE Climate as of 9/5/24.

The affordability of the tax increase is tied to the city’s credit rating. Virginia Beach currently has a AAA credit rating: if its rating was lower, the property tax increases required to service the debt payments on this issuance might have been significantly larger.19

In many cases, downgrades occur when the ratings agency views the municipality as over-leveraged, or in too much debt.20 Debt service obligations were cited as one reason for S&P’s downgrade of New Haven, Connecticut, in 2018,21 for example, and as a factor in Fitch’s 2024 decision to downgrade some of the municipal bonds issued by Wilmington, Delaware,22 as well as Moody’s 2023 decision to downgrade Honolulu, Hawaii.23 On the flip side, the full repayment of debt obligations has also helped lead to credit rating upgrades for municipalities.24

Across the country, city hall officials’ concerns about ratings actions often make local news.25,26,27,28 These worries are justifiable — credit downgrades can have add-on financial and political effects, often causing accusations of mismanagement from residents as the municipality’s borrowing costs increase.

But for climate adaptation infrastructure projects, could a downgrade be worth it?

The costs of a hypothetical downgrade for Virginia Beach

Using ICE Pricing & Reference Data, we estimated borrowing costs associated with various credit ratings for the principal amount associated with Virginia Beach’s approved $567.5 million flood mitigation bond. To simplify the calculation, we assumed that the city issued a single bond to fund the project that is repaid over 30 years.

Based on a recent example date,29 the average yield for a 30-year AAA-rated municipal bond was 3.81% according to ICE Pricing & Reference Data, while the average yield for a 30-year BB-rated municipal bond was 5.20%. Applying these yields to a principal amount of $567.5 million, the estimated annual debt service required for an issuer with a AAA-rating would be about $32 million, while the estimated annual debt service for an issuer with a BB-rating would be about $38 million – a difference of about $6 million annually (Table 1).

Over the course of this 30-year period, the estimated aggregate debt service paid by an issuer with a AAA-rating would be about $961 million, while the estimated aggregate debt service paid by an issuer with a BB-rating would be over $1 billion – a net difference of about $170 million.

Virginia Beach Flood Mitigation Bond

Principal amount: $567,500,000

| Average yield (30 year) | Annual debt service (30 year) | Aggregate debt service (30 year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | 3.81% | $32,053,888 | $961,616,645 |

| BB | 5.20% | $37,749,823 | $1,132,494,679 |

| Difference | 1.39% | $5,695,934 annually | $170,878,034 over 30 years |

Table 1. Breakdown of approximate debt service costs for an issuer with a AAA-rating and an issuer with a BB-rating for a hypothetical $567.5 million issuance with a 30-year maturity. Source: ICE Pricing & Reference Data as of 1/6/25.

Comparison of Total Costs & Cost of No Intervention

Figure 2. Hypothetical costs associated with issuing Virginia Beach’s $567.5 million flood mitigation bond on an example date of January 6, 2025, as a single security with a 30-year maturity with a AAA credit rating and a BB credit rating including debt service, alongside the projected $4.6 billion in losses associated with no intervention.30 Source: ICE Climate as of 1/6/25.

In the Virginia Beach example, it still makes sense to issue the bond, regardless of the credit rating. The estimated costs of a downgrade ($170 million over a 30-year period) pale in comparison to the estimates of the losses from flooding with no intervention ($4.6 billion over a 48-year period).31, 32 Put another way, the aggregate loss due to a downgrade is essentially nothing compared to the potential costs of doing nothing.

Even when the entirety of Virginia Beach’s five-year Capital Improvement Plan33 covering fiscal years 2025-2030 is taken into account, the benefits of adaptation infrastructure likely still outweigh the estimated costs of a potential downgrade. According to the plan, the city will issue about $874 million in debt over the next five years. If we assume that this annual rate continues for the next 30 years, the aggregate additional debt service associated with a theoretical downgrade (Table 2) would amount to less than half of the value of the projected losses from flooding with no intervention.

Virginia Beach Total Capital Improvement Plan Debt Financing (30-Year Projection)

Principal amount: $5,245,000,000

| Average yield (30 year) | Annual debt service (30 year) | Aggregate debt service (30 year) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAA | 3.81% | $296,251,354 | $8,887,540,625 |

| BB | 5.20% | $348,894,837 | $10,466,845,098 |

| Difference | 1.39% | $52,643,482 annually | $1,579,304,473 over 30 years |

Table 2. Breakdown of approximate debt service costs for an issuer with a AAA-rating and an issuer with a BB-rating for a hypothetical $5.245 billion issuance with a 30-year maturity assuming the average yields included in the table. The aggregate principal amount was estimated by taking the projected debt financing costs for the next five years ($874.2 million) in the city’s 2024-2025 Capital Improvement Plan and assuming the same rate of annual debt-financed investments over a 30-year period. Source: ICE Pricing & Reference Data as of 1/6/25.

Borrowing hundreds of millions of dollars to build climate adaptation infrastructure could save the municipality and its residents hundreds of millions of dollars in the long run, even if the city were to lose its AAA credit rating as a result.

Cost-benefit analyses should include debt affordability

Other cities across the United States are currently weighing the costs and benefits of climate adaptation infrastructure. The city of Charleston is working to build tunnels, pump stations, and raise its current sea wall to protect itself against increasing flood risks.34 New York City is already funding climate adaptation projects across several boroughs to protect itself from coastal flood risks, many of which were initiated in response to the substantial damage caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.35 A neighboring coastal community to Virginia Beach, the city of Norfolk, is commissioning the Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management Project, funding a floodwall, storm-surge barriers, and other climate adaptation projects, with projected annual net benefits of $122 million once completed.36

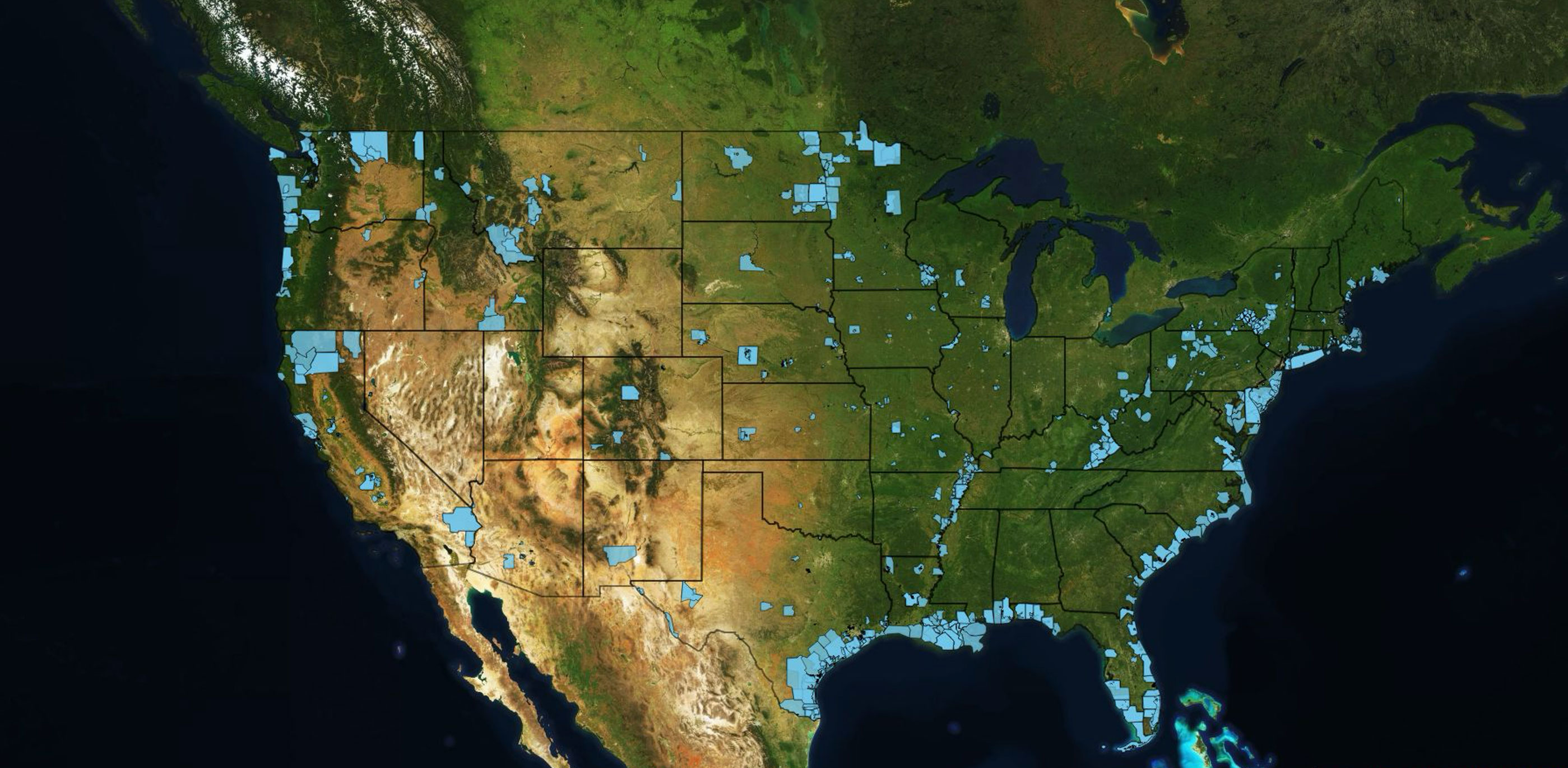

Figure 3. Obligor boundaries with areas less than 10,000 square miles and ICE Flood Scores greater than 3.5. Source: ICE Climate as of 9/5/24.

Virginia Beach illustrates the importance of viewing the costs and benefits of climate adaptation projects through as broad of a lens as possible — explicitly considering the potential effects of a downgrade as well as the projected costs of inaction. The risks of being over-leveraged should be evaluated quantitatively against projected costs associated with physical climate risks. In some cases, the protection provided by climate adaptation infrastructure may be worth the risk of a downgrade. Going forward, credit rating agencies may need to clarify how they weigh the protective effects of climate adaptation infrastructure against the credit risk of debt liabilities.

Importantly, these high-profile examples of climate adaptation projects and proposals tend to be in densely populated and well-funded municipalities (Virginia Beach had a median household income of over $87,000 in 2022, well above the nationwide average).37 Low-income and rural areas may often face an entirely different set of challenges, including a lack of financial resources to conduct cost-benefit analyses and solicit proposals, high per capita costs for infrastructure, larger land areas, and prohibitively high borrowing costs. Protecting communities in these areas will likely require federal and state involvement through bond banks, credit enhancement programs, direct loans, or grants.

While a downgrade may be worth it for some cities, many of these rural areas lack a credit rating entirely. Given the increase in frequency and severity of climate events, our analysis demonstrates that when the full costs and benefits are taken into account, investing in climate adaptation infrastructure can often be crucial for protecting vulnerable communities – even with the possibility of a downgrade.

1 The City of New York. (2013, June 11). A Stronger, More Resilient New York. NYC Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency. http://s-media.nyc.gov/agencies/sirr/SIRR_singles_Hi_res.pdf

2 2020 Case Study 2: The 2019 Floods in the Central U.S. Lancet Countdown. (2021, February 2). https://www.lancetcountdownus.org/2020-case-study-2/

3 Storrow, B. (2023, October 11). Vermont struggles to recover 3 months after record flooding. E&E News by POLITICO. https://www.eenews.net/articles/vermont-struggles-to-recover-3-months-after-record-flooding/

4 Blood, M. R. (2023, June 5). California insurance market rattled by withdrawal of major companies. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/california-wildfire-insurance-e31bef0ed7eeddcde096a5b8f2c1768f

5 Allen, G. (2025, January 13). California’s wildfires may also be catastrophic for its insurance market. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/01/13/nx-s1-5256381/californias-wildfires-insurance-market

6 NOAA. (2022, September 7). Hurricane Katrina - August 2005. National Weather Service. https://www.weather.gov/mob/katrina

7 Albright, A. (2024, August 19). Texas Drought Forces Small Town to Default on Water System Debt. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-08-19/texas-drought-forces-small-town-to-default-on-water-system-debt

8 Paradise Redevelopment Agency, CA Series 2009 Refunding Tax Allocation Bond Rating Lowered To “D” On Payment Default. S&P Global Ratings. (2023, June 1). https://disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/id/2995197

9 Alfini, M. (2024, May 29). To keep floodwaters out, Charleston is designing a sea wall. WSOC TV. https://www.wsoctv.com/news/local/keep-floodwaters-out-charleston-is-designing-sea-wall/FSICWU3EU5DCZBCN4BOZZAEW7M/

10 Municipal Market Analytics - Daily Strategist. Municipal Market Analytics. (2024, March 18).

11 Methodology For Rating U.S. Governments. S&P Global Ratings. (2024, September 9). https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/ratings/research/101604201.pdf

12 US Municipal Bond Defaults and Recoveries, 1970-2022. Moody’s Investors Service. (2023, July 19). https://www.fidelity.com/bin-public/060_www_fidelity_com/documents/fixed-income/moodys-investors-service-data-report-us-municipal-bond.pdf

13 Climate change is forecast to heighten US exposure to economic loss placing short- and long-term credit pressure on US states and local governments. Moody’s Ratings. (2017, November 28). https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-Climate-change-is-forecast-to-heighten-US-exposure-to-Announcement--PR_376056

14 Making Virginia Beach “Sea Level Wise.” NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (n.d.). https://coast.noaa.gov/states/stories/sea-level-wise.html

15 Steinhilber, E. (2021, December 10). Virginia Beach’s new flood bond can be a model for other cities. here’s how. Environmental Defense Fund: Growing Returns. https://blogs.edf.org/growingreturns/2021/12/10/virginia-beach-bond-model-cities/

16 McNab, R., Yusuf, J.-E., Anuar, A., & Whitehead, J. (2021, September 27). Virginia Beach Flood Protection Program Bond Referendum Analysis. Old Dominion University Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience. https://oduadaptationandresilience.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Virginia-Beach-Flood-Protection-Program-Bond-Referendum-Analysis-9_27_21.pdf

17 McNab, R., Yusuf, J.-E., Anuar, A., & Whitehead, J. (2021, September 27).

18 Steinhilber, E. (2021, December 10).

19 The town did face the prospect of a potential downgrade in 2014, when Moody’s reached out to the city to ask about its sea level rise vulnerabilities, expenses, and plans to address future impacts. At the time, the city had recently developed a program dedicated to addressing rising sea levels. These efforts satisfied Moody’s and the city kept its high rating. (Source)

20 Methodology For Rating U.S. Governments. S&P Global Ratings. (2024, September 9). https://www.spglobal.com/_assets/documents/ratings/research/101604201.pdf

21 Breen, T. (2018, July 25). S&P Downgrades City Credit Rating. New Haven Independent. https://www.newhavenindependent.org/article/sp_downgrades_city_credit_rating_

22 Castagno, P. (2024, June 18). Fitch Ratings downgrades Wilmington’s municipal bonds. Port City Daily. https://portcitydaily.com/local-news/government/2024/06/18/fitch-ratings-downgrades-wilmingtons-municipal-bonds/

23 Daysog, R. (2023, March 3). Firm downgrades city’s bonds for first time since 1999, citing rail debt. Hawaii News Now. https://www.hawaiinewsnow.com/2023/03/03/firm-downgrades-citys-bonds-first-time-since-1999-citing-growing-rail-debt/

24 Petersburg Receives Bond Rating Upgrade to “BBB+”; Outlook Remains ‘Positive.’ City of Petersburg, Virginia. (2021, March 22). https://www.petersburgva.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=1295&ARC=2032

25 Koosau, M. (2024, March 1). Jersey City credit rating downgraded; emergency spending and control issues cited. The Jersey Journal. https://www.nj.com/hudson/2024/03/jersey-city-credit-rating-downgraded-emergency-spending-and-control-issues-cited.html

26 Moody’s Downgrade Exposes City’s Deep Fiscal Woes. Radio Free Richmond. (n.d.). https://www.radiofreerichmond.com/moody_s_downgrade_exposes_city_s_deep_fiscal_woes

27 Wolcott, B., & Orr, S. (2019, December 11). Moody’s cuts Rochester’s debt rating, blames RCSD’s “poor budgeting.” Democrat and Chronicle. https://www.democratandchronicle.com/story/news/2019/12/10/rochester-ny-moodys-debt-rating-rcsd-school-district-finances/4388661002/

28 Helton, J. (2023, April 7). Rail debt gimmick comes back to bite Honolulu taxpayers. Honolulu Civil Beat. https://www.civilbeat.org/2023/04/rail-debt-gimmick-comes-back-to-bite-honolulu-taxpayers/

29 January 6, 2025.

30 McNab, R., Yusuf, J.-E., Anuar, A., & Whitehead, J. (2021, September 27).

31 These projections were provided in 2021 dollars.

32 McNab, R., Yusuf, J.-E., Anuar, A., & Whitehead, J. (2021, September 27).

33 City of Virginia Beach Capital Improvement Program: Proposed FY 2024-25. City of Virginia Beach. (2024). https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/virginia-beach-departments-docs/budget/Budget/Proposed/FY-2025/FY25-Proposed-CIP-Budget.pdf

34 Mellen, R., & Dance, S. (2024, August 6). In Charleston, Floods are a “Constant Existential Fear.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2024/08/06/charleston-debby-flooding-curfew/

35 Lewis, A. S. (2023, December 19). After a decade of planning, New York City is raising its shoreline. Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/new-york-city-climate-plan-sea-level-rise

36 Little, V. (2019, July 1). Leaders sign Norfolk Coastal Storm Risk Management design agreement. US Army Corps of Engineers Norfolk District Website. https://www.nao.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Stories/Article/1892903/leaders-sign-norfolk-coastal-storm-risk-management-design-agreement/

37 Virginia Beach City, VA. Data USA. (2022). https://datausa.io/profile/geo/virginia-beach-city-va